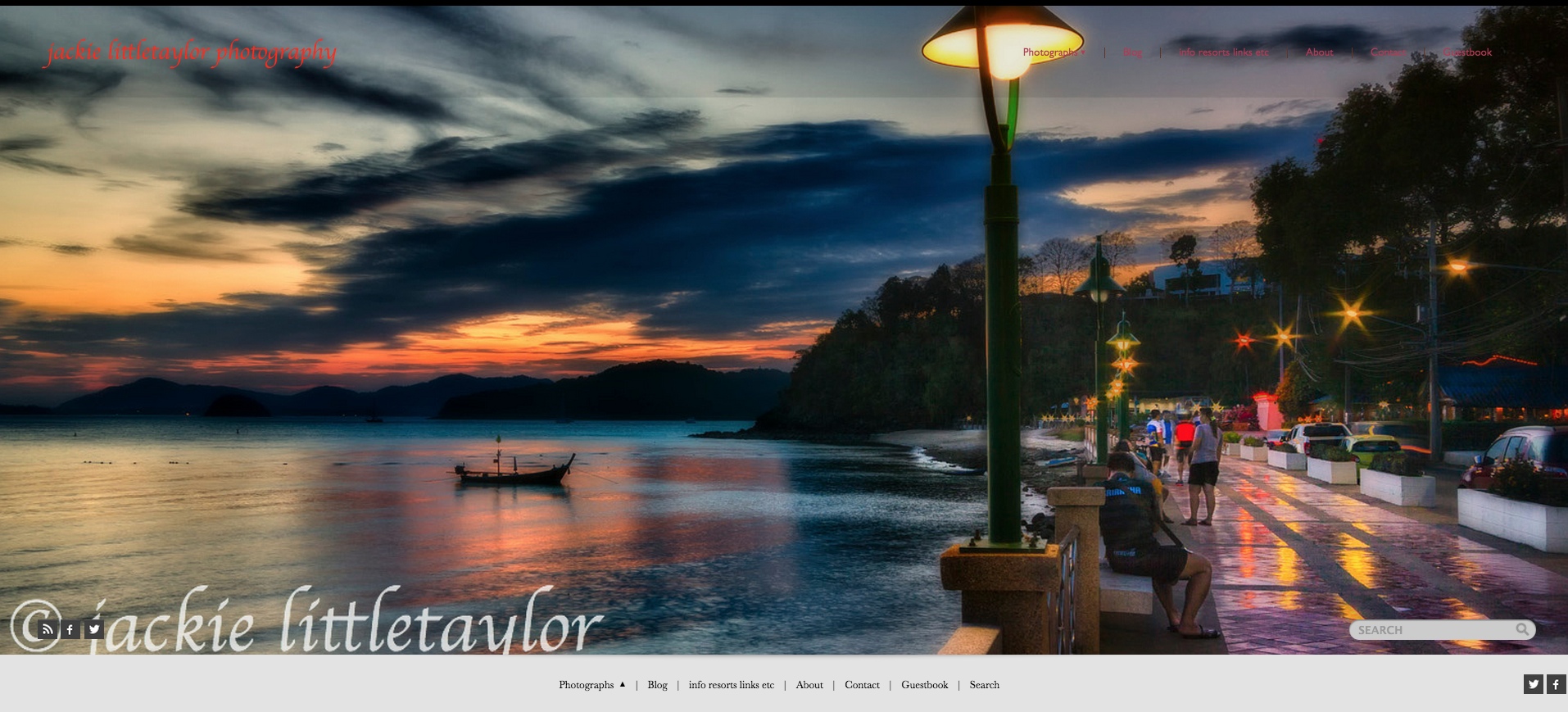

All of us here at Life SE Asia believe the future for any country depends on its citizens to have a good education. We are fortunate to have as one of our members a teacher from England that has been teaching in Thailand for several years and will be informing us as we go along. Kris is also a good photographer, so will enjoy his photography as well. Please ask questions or your concerns and we will try to address them.

Text and the source is from

Southeast Asia

Indigenous culture, colonialism, and the post-World War II era of political independence influenced the forms of education in the nations of Southeast Asia—Myanmar (Burma), Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore,Thailand, and Vietnam.

Before 1500 ce, education throughout the region consisted chiefly of the transmission of cultural values through family and community living, supplemented by some formal teaching of each locality’s dominant religion—animism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, or Islam. Religious schools typically were attended by boys living in humble quarters at the residence of a pundit who guided their study of the scriptures for an indeterminate period of time.

With the advent of Western colonization after 1500 and particularly from the early 19th to the mid-20th century, Western schooling—with its dominantly secular curriculum, sequence of grades, examinations, set calendar, and diplomas—began to make strong inroads on the region’s traditional educational practices. For the indigenous peoples, Western schooling had the appeal of leading to employment in the colonial government and in business and trading firms.

After World War II, as all sectors of Southeast Asia gained political independence, each newly formed country attempted to achieve planned development—to furnish primary schooling for everyone, extend the amount and quality of post primary education, and shift the emphasis in secondary and tertiary education from liberal, general studies to scientific and technical education. Although indigenous culture was still learned through family living and traditional religion continued to be important in people’s lives, most formal schooling throughout Southeast Asia had become predominantly of a Western, secular variety.

Schooling in all these countries was organized into three main levels: primary, secondary, and higher. In addition, nursery schools and kindergartens, operated chiefly by private groups, were gradually gaining popularity. The typical length ofprimary schooling was six years. Secondary education was usually divided into two three-year levels. A wide variety of postsecondary institutions offered academic and vocational specializations. Beginning in the 1950s, nonformal education to extend literacy and vocational skills among the adult population expanded dramatically throughout the region. Most of the countries were committed to compulsory basic education, typically for six years but up to nine years in Vietnam. However, the inability of governments to furnish enough schools for their growing populations prevented most from fully realizing the goal of universal basic schooling.

In each country a central ministry of education set schooling structures and curriculum requirements, with some responsibilities for school supervision, curriculum, and finance often delegated to provincial and local educational authorities. Government-sponsored educational research and development bureaus had been established from the 1950s in an effort to make the countries more self-reliant in fashioning education to their needs. Regional cooperation in attacking educational problems was furthered by membership in such alliances as the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). The problems that most Southeast Asian education systems continued to face were reducing school dropout and grade-repeater rates, providing enough school buildings and teachers to serve rapidly expanding numbers of children, furnishing educational opportunities to rural areas, and organizing curricula and access to education in ways that suited the cultural and geographical conditions of multiethnic populations.

You can reach Kris here or visit his web site at Native English Teacher Online

to read more about Education in SE Asia and Asean Education go to

ASEAN Education - The Rise of the ‘Glocal’ Student